Quant hedge funds reject the vast majority of alt data they evaluate, but often not for the reasons data providers assume. This article explains how systematic funds evaluate third-party datasets, why trials often fail, and what determines whether a provider’s data is tested, trusted and ultimately deployed.

Quant funds are constantly pitched new datasets. Each pitch follows a familiar structure: this data is predictive, and buying it will improve trading performance.

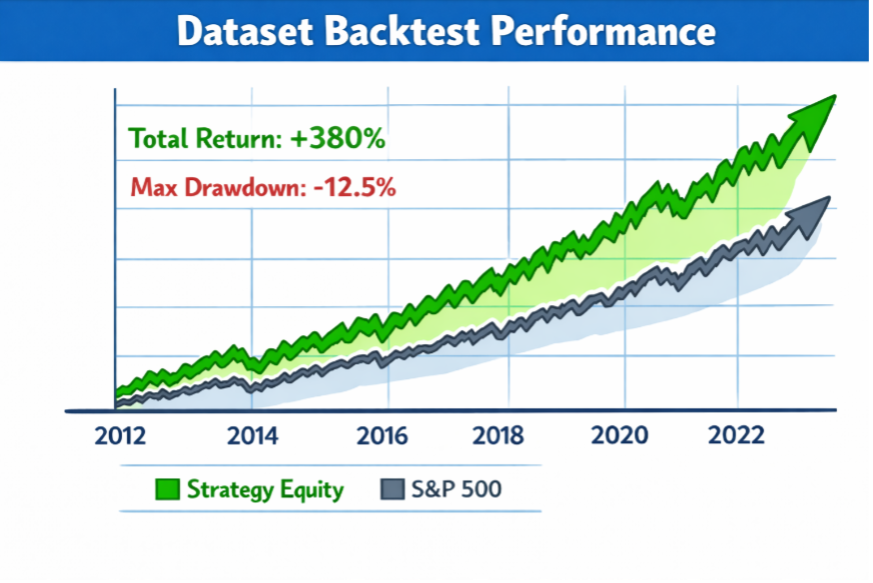

Providers commonly illustrate this claim with backtests – analyses designed to show how a trading strategy based on their data would have performed historically. Almost every data provider’s backtest looks like this:

Unfortunately, live results often fail to match backtested performance once funds start trading on the data.

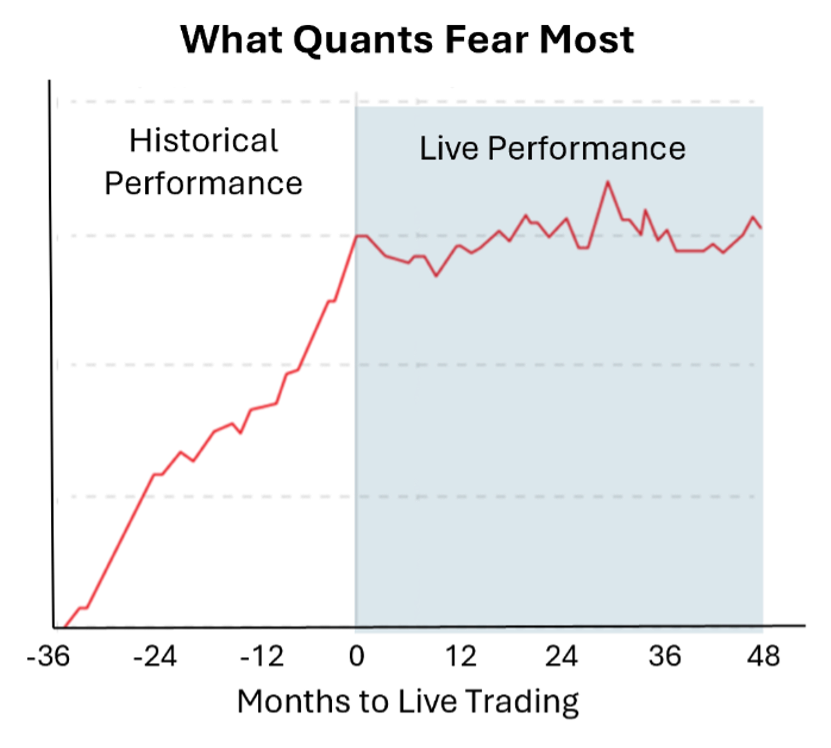

Quant investing is inherently statistical. Many strategies that look promising in-sample fail very expensively in live trading (out-of-sample). Even sound strategies with strong live records experience periods of underperformance, making short-term results difficult to distinguish from noise.

A quant manager’s central challenge is developing enough conviction in a model to stay invested through periods of noise and underperformance. If a model cannot be trusted at scale, it is quickly deprioritized.

Funds use backtests to evaluate potential trading strategies, and backtests are only as reliable as the historical inputs they depend on. Those inputs are rarely fixed. Methodologies evolve. Records are revised. Companies enter and exit the coverage universe. Timestamps fail to reflect when funds could have traded on the data.

This is why the first questions quant funds ask about third-party data are often about provenance: how methodology has changed over time, how revisions are tracked, and what timestamps mean in practice.

Given these challenges -- and many investors’ history of false positives from underperforming strategies -- funds use live trials to build confidence in third-party data. But trials are a blunt and expensive tool.

Evaluating a dataset via trial requires scarce engineering, research, and operational resources. For large funds, the direct and indirect (opportunity) cost of a data trial can be substantial – often comparable to the cost of the data itself.

Even when trials occur, they are often too brief to separate signal from noise, causing many datasets to fail trials for reasons unrelated to actual dataset quality.

Quant investors are used to working with imperfect data. In fact, cleaning messy data can be a source of competitive advantage. Broken causality, however, cannot be easily repaired and is the core failure mode behind many stalled data evaluations.

Broken causality occurs when an analyst cannot reliably determine which version of the data was available at the point-in-time of a backtested trading decision. Even a dataset of perfect earnings forecasts for public companies may not be usable in a trading context if a fund cannot determine with certainty whether the data was available before the earnings announcement. A one-minute timing lag can make the difference between millions in profit and millions in losses.

The same issue occurs when coverage expands, identifiers are remapped, or backfilled values appear in the data before they were actually known.

Causality is frequently undermined by subtle, seemingly beneficial operations such as historical revisions, methodology updates, versioning, and timestamp adjustments. When causality in third-party data is ambiguous, the chain of cause-and-effect collapses, and investors lose confidence in all derived data and signals. As a result, funds routinely walk away from promising high-signal datasets without even a trial.

Consider a mid-sized systematic hedge fund evaluating a dataset of historical sales indicators for large technology companies. The dataset is well-constructed, professionally maintained, and shows strong backtest performance across multiple historical periods.

During a three-month trial, however, the live performance of trading rules based on the data is modest and inconsistent.

The research team asks the provider about historical revisions and methodology changes. The provider offers reasonable explanations but no means for the fund to verify them. Uncertainty creeps in as the fund’s research team notices small discrepancies between historical and live data. Compounding the issue is the fund’s prior experience with historical performance that failed to translate into live results.

The fund labels the trial inconclusive and decides not to proceed with purchasing the data. Both sides expend considerable time and effort without gaining clarity on the cause of the trial failure. The fund couldn’t determine whether the issue was with the signal itself or uncertainty about the historical record.

Consider the same scenario, but with historical data that is transparent and well-documented. The buyer can now evaluate the dataset using the data’s full historical record rather than a limited trial window.

If live performance underwhelms during a three-month trial, the team can be more confident in attributing the result to statistical noise rather than uncertainty around historical integrity. Trial performance is now a small component of the overall purchase decision rather than the critical indicator of live performance.

In this scenario, the data itself didn’t change. Only the fund’s confidence in its own evaluation process has improved. This helps the team decide whether the dataset merits deeper research investment.

In systematic workflows, you’re not just selling “a dataset”,usability and reproducibility often matter as much as the underlying signal.

A few practical tips for providers:

Following these suggestions doesn’t guarantee buyer engagement, but it significantly reduces the chances of stalled evaluations.

If you’re not sure where your dataset falls on these dimensions, a simple diagnostic is: can a buyer independently reconstruct what your dataset looked like on any past date, including what changed since then and why? If the answer is “not reliably,” that’s often where evaluations stall.

Greater historical transparency changes the economics of data evaluation. Funds are more willing to engage and do so earlier because the risk of wasted research effort is materially lower. The fund’s most common evaluation concerns are addressed sooner in the process.

As buyer confidence increases, willingness to allocate budget and research resources tends to increase as well. The data shifts from being “interesting” to something a research team can defend internally and deploy to production.

Improved historical defensibility doesn’t change the underlying information content of the data. It changes how confidently data buyers can interpret their own research results. That confidence is often the difference between an inconclusive trial and sustained adoption.

If you would like to learn more about these problems, I am happy to share a checklist that can help you get your dataset ready for evaluation by a prospective buyer.

Dan Averbukh is the co-founder and CEO of validityBase, where he works on data reliability and evaluation infrastructure for systematic investing.

Monetize data, fuel AI: More than 150 companies use Monda's all-in-one data monetization platform to turn data into products into revenue.

Explore platformMonda makes it easy to create, customize, and share AI-ready data products. Find out more about data sharing and company news on our blog.

Sign up to Monda Monthly to get data & AI thought leadership, product updates, and event notifications.